In July, President Obama met for 45 minutes with leaders of American Jewish organizations. All presidents meet with Israel’s advocates. Obama, however, had taken his time, and powerhouse figures of the Jewish community were grumbling; Obama’s coolness seemed to be of a piece with his willingness to publicly pressure Israel to freeze the growth of its settlements and with what was deemed his excessive solicitude toward the plight of the Palestinians. During the July meeting, held in the Roosevelt Room, Malcolm Hoenlein, executive vice chairman of the Conference of Presidents of Major American Jewish Organizations, told Obama that “public disharmony between Israel and the U.S. is beneficial to neither” and that differences “should be dealt with directly by the parties.” The president, according to Hoenlein, leaned back in his chair and said: “I disagree. We had eight years of no daylight” — between George W. Bush and successive Israeli governments — “and no progress.”

It is safe to say that at least one participant in the meeting enjoyed this exchange immensely: Jeremy Ben-Ami, the founder and executive director of J Street, a year-old lobbying group with progressive views on Israel. Some of the mainstream groups vehemently protested the White House decision to invite J Street, which they regard as a marginal organization located well beyond the consensus that they themselves seek to enforce. But J Street shares the Obama administration’s agenda, and the invitation stayed. Ben-Ami didn’t say a word at the meeting — he is aware of J Street’s neophyte status — but afterward he was quoted extensively in the press, which vexed the mainstream groups all over again. J Street does not accept the “public harmony” rule any more than Obama does. In a conversation a month before the White House session, Ben-Ami explained to me: “We’re trying to redefine what it means to be pro-Israel. You don’t have to be noncritical. You don’t have to adopt the party line. It’s not, ‘Israel, right or wrong.’ ”

There appears to be an appetite for J Street’s approach. Over the last year, J Street’s budget has doubled, to $3 million; its lobbying staff is doubling as well, to six. That still makes it tiny compared with the American Israel Public Affairs Committee, or Aipac, whose lobbying prowess is a matter of Washington legend. J Street is still as much an Internet presence, launching volleys of e-mail messages from the netroots, as it is a shoe-leather operation. But it has arrived at a propitious moment, for President Obama, unlike his predecessors, decided to push hard for a Mideast peace settlement from the very outset of his tenure. He appointed George Mitchell as his negotiator, and Mitchell has tried to wring painful concessions from Israel, the Palestinians and the Arab states. In the case of Israel, this means freezing settlements and accepting a two-state solution. Obama needs the political space at home to make that case; he needs Congress to resist Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s appeals for it to blunt presidential demands. On these issues, which pose a difficult quandary for the mainstream groups, J Street knows exactly where it stands. “Our No. 1 agenda item,” Ben-Ami said to me, “is to do whatever we can in Congress to act as the president’s blocking back.”

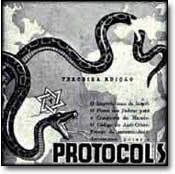

The idea that there is an “Israel lobby,” with its undertones of dual loyalty, is a controversial notion. It has been around since the early 1970s at least, but it became a topic of wide discussion only after the publication of a notorious article in The London Review of Books in 2006 by the political scientists John Mearsheimer and Stephen Walt. The article, which was expanded into a book, infuriated many readers by its air of conspiratorial hugger-mugger; by its insistence that Jewish neoconservatives had persuaded President Bush to go to war in Iraq in order to protect Israel; and by the authors’ apparent ignorance of the deep sense of identification many Americans — Jewish and gentile — feel toward Israel. But the authors made one claim that struck many knowledgeable people as very close to the mark: The Israel lobby had succeeded in ruling almost any criticism of Israel out of bounds, especially in Congress.

“The bottom line,” Mearsheimer and Walt wrote, “is that Aipac, a de facto agent for a foreign government, has a stranglehold on Congress, with the result that U.S. policy is not debated there, even though that policy has important consequences for the entire world.” Mearsheimer and Walt also wrote that Aipac and other groups succeeded in installing officials who were deemed “pro-Israel” into senior positions. This is, of course, what effective lobbies do. The Cuba lobby, for example, long operated in the same way. But Israel is a much more important American national-security interest than Cuba. No country, whether Israel or Cuba, has identical interests to those of the United States. And yet mainstream American Jewish groups had implicitly agreed to subordinate their own views to those of the government in Jerusalem. The watchword, says J. J. Goldberg, editorial director of The Forward, the Jewish weekly, was, “We stick with Israel regardless of our own judgment.”

American Jewish voters are overwhelmingly liberal and Democratic, but as Jewish groups moved to the right along with Israel in the 1980s, the groups increasingly made common cause with the Republican Party, which from the time of Ronald Reagan was seen as more staunchly pro-Israel than were the Democrats. Jewish groups also began to work with the evangelicals who formed the Republican base and tended to be fervidly pro-Israel. Indeed, when I met with Malcolm Hoenlein in July, he had just come from a huge Washington rally sponsored by Christians United for Israel, whose founder, the Rev. John Hagee, has denounced Catholicism, Islam and homosexuality in such violent terms that John McCain felt compelled eventually to reject his endorsement during the 2008 presidential campaign.

George W. Bush shared the views of the mainstream groups on Israel and Palestine, on Iran and on the threat of Islamic extremism. Doug Bloomfield, who served as legislative director for Aipac in the 1980s — and who was pushed out, he says, for being “too pro-peace” — describes Aipac and other groups as “very sycophantic toward the Bush administration.” Aipac and other groups found little to criticize in a president who, unlike Bill Clinton, did not believe in pushing Jerusalem to make serious compromises to achieve peace. President Bush, in this view, was the best president either Israel’s Likud leadership or the mainstream Jewish groups could have wished for.

And it was precisely this success that began to loosen the “stranglehold” described by Mearsheimer and Walt. As Martin Indyk, a former American ambassador to Israel and now the director of foreign policy at the Brookings Institution, puts it, “In the Bush years, when Israel enjoyed a blank check, increasing numbers of people in the Jewish and pro-Israel community began to wonder, If this was the best president Israel ever had, how come Israel’s circumstances seemed to be deteriorating so rapidly?” Why was Israel more diplomatically isolated than ever? Why had Israel fought a savage and apparently unavailing war with Hezbollah in Lebanon? Why were the Islamists of Hamas gaining the upper hand over the more moderate Fatah in Palestine? “There was kind of a cognitive dissonance,” Indyk says, “about whether a blank check for Israel is necessarily the best way to secure the longevity of the Jewish state. More here:

http://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/13/magazine/13JStreet-t.html?pagewanted=2&_r=1

There's a New AIPAC in Town and We Want A Potato Blight Museum in Washington!

Monday, 14 September 2009

The New Israel Lobby

Posted @

18:43

![]()

Post Title: The New Israel Lobby

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

![[9_10_s22.jpg]](https://blogger.googleusercontent.com/img/b/R29vZ2xl/AVvXsEjTXnQay9wzz0E6nVHrVhaHKoq_zYXDqZjijHlNDQzj90MZzInrCuVX4ciFYCiBfZ7lhlgr2bBhhnl7ddWbhdih5JbXjQYbA605TNyiq046bQqjG2A4S-nHTmh1VBTQSG6tmc23wq47QQ/s1600/9_10_s22.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment